The Off-Switch for Climate Change

Abolishing fossil fuels is a clear and concise demand commensurate with the size of the problem. Why do we never hear anyone talk about it?

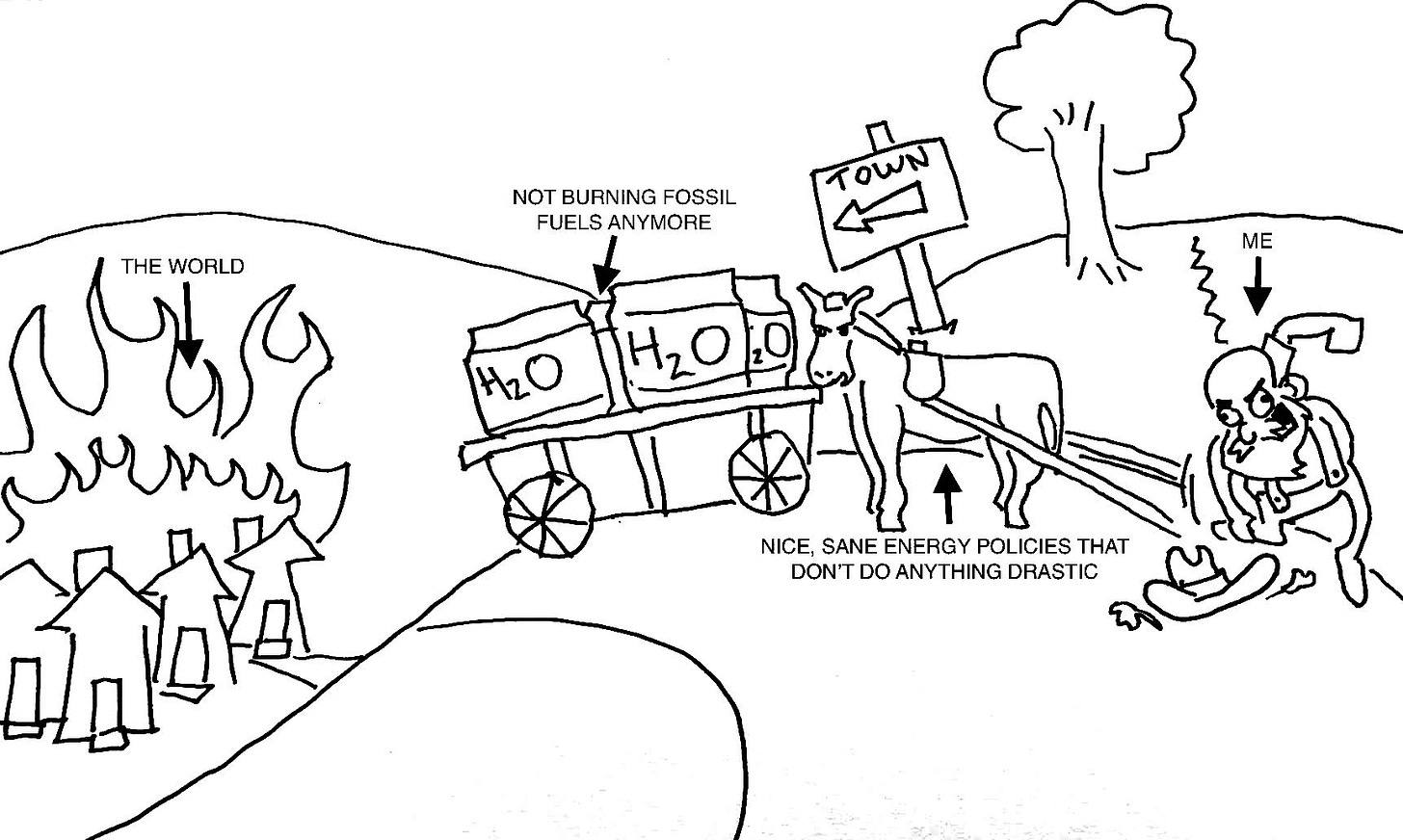

(photo by the author)

NOTE: This is a newsletter. Please pretend I’m not letting you read this unless you subscribe. I won’t actually stop you from reading it if you don’t subscribe, and in either case it’s free, but please subscribe anyway. Thank you!

“Joe Biden and Kamala Harris want to abolish fossil fuels,” Mike Pence said in a tweet on October 17. They don’t, of course, and they strenuously deny that even fracking will be touched if Biden is elected. Biden prefers modest climate reforms. Abolishing fossil fuels is too crazy, the thinking goes. Nice, sane energy policies will carry us all safely us to the sustainable future. The abolition of fossil fuels, instead of the slow, methodical, asymptotic phase-out, is putting the cart before the horse, the thinking goes.

But the horse in the cart-before-the-horse analogy is a worthless horse who has steadfastly refused, for decades, to get in front of the cart. And to make matters worse, the cart is full of water, and the town is on fire.

Here, I made a diagram:

A sudden, total ban on fossil fuels would be like kicking the cart down the hill. General chaos is one obvious side effect, but similar chaos is a side effect of out-of-control climate change too and that’s what we’re getting. At least “ban all fossil fuels ASAP” is a clear answer commensurate to the scope of the problem. Contemplating it from time to time would, I think, lead to clearer thinking and a greater sense of urgency.

In 2008, Greenpeace proposed a fossil-free world by 2090, but the world didn’t pay much attention to their gentle urging and their 82-year timeline. I submit that it might stir things up if they revisited the idea, but this time proposed, say, a five-year timeline. British journalist Leo Hickman of Carbon Brief came close to this sort of thing when his site released this animation last year, showing what ramping down emissions in time to keep warming down to 1.5 degrees would look like:

I know it may seem like there’s light at the end of the tunnel because of some symbolic promises politicians have been making lately. France, after all, is banning all fossil fuel extraction in 20 years! California is promising an all-green electric grid in 25 years! But if you think Carbon Brief is exaggerating, or that things are going well, and fossil fuels are being ramped down successfully through the power of market-friendly solutions—think again. Deloitte’s May 2020 report on the energy transition paints a depressing picture: At the moment, renewables are producing about 17.5 percent of grid energy in the US, and they only expect that number to go up to 38 percent by 2050.

Given the absence of the climate miracle we’ve all been waiting for; given the likelihood of another Republican presidential administration or five over the next few decades; given the obstructionism of conservatives all over the world; and given the reluctance of developing countries like, to name one random example, Kazakhstan to give up cheap greenhouse gas-intensive energy sources like coal, 3 degrees is a more reasonable forecast for our planet’s future than 1.5 or 2. Four degrees of warming is very much on the table. Five degrees? Not out of the question.

Pick your own scary climate change explainer if you need to be reminded why this is a nightmare. If you don’t have one close at hand, here’s the most vivid paragraph in David Wallace-Wells’s The Uninhabitable Earth:

Two degrees would be terrible, but it’s better than three, at which point Southern Europe would be in permanent drought, African droughts would last five years on average, and the areas burned annually by wildfires in the United States could quadruple, or worse, from last year’s million-plus acres [Note: It has already quadrupled since this passage was written]. And three degrees is much better than four, at which point six natural disasters could strike a single community simultaneously; the number of climate refugees, already in the millions, could grow tenfold, or 20-fold, or more; and, globally, damages from warming could reach $600 trillion—about double all the wealth that exists in the world today. We are on track for more warming still—just above four degrees by 2100, the U.N. estimates. So if optimism is always a matter of perspective, the possibility of four degrees shapes mine.

And if that doesn’t make you want to kick the proverbial cart of water down the hill to douse the flaming village, keep in mind that this is old news to our leaders. They didn’t just learn about this stuff during the 2020 Democratic primary, or when Wallace-Wells’s big scary New York Magazine article came out in 2017. They’ve known the extent of this problem for half a century.

In a 1968 defense report funded by the federal government, the analyst Gordon J. F. MacDonald wrote, “Carbon dioxide placed in the atmosphere since the start of the industrial revolution has produced an increase in the average temperature of the lower atmosphere of a few tenths of a degree Fahrenheit.” Those words were written before Woodstock. The Department of Energy created a now-defunct Office of Carbon Dioxide Environmental Effects around the time the original Star Wars was in theaters. Pretty much everything we understand about the high stakes of climate change today was fully fleshed out in a 1979 report written under the aegis of the National Research Council, around the same time Post-Its started being sold. In 1988, just as the first season of The Wonder Years was gracing TV screens across America, climate scientist James Hansen testified before congress that global warming had already begun, and it made the front page of The New York Times.

And all this time later, when asked about climate change, our supreme overlords can still give responses like, “I would not say I have firm views on it,” and somehow not be pelted with old vegetables, because that’s the orthodoxy of their cultish political party. (Their excuse is that they pretend to believe climate change is fake).

The institutions the govern our lives for us have done essentially nothing to stop a problem we’ve known about for decades. The best of them are continuing to slow-walk, and the worst of them are actively making it worse.

I may just be an idiot with a newsletter, but the more time goes by, and the worse this problem gets, the more black-and-white thinking seems appropriate. Abolishing fossil fuels is a far-off goal, and you can use some dismissive term if you want like “magic wand” or “off-switch,” but that really is what we need to do. (And in the process, hopefully we can see our way clear to making the drastic and necessary reforms we need to see in agriculture as well, but fossil fuels are the 800-pound gorilla in the room).

As an antidote to these impasses, the complexity, the grandstanding, and to our general sense of hopelessness around this issue, I’d like to introduce you to some people I learned about a while ago who can lend a little clarity thanks to their super catchy climate plan: turn climate change off at the source with a pair of bolt cutters and maybe even a big monkey wrench.

In January, the Department of Homeland Security branded this group, called “Valve Turners,” with the label “extremists,” and I branded them with the label “very cool.” Valve Turners—actually just a handful of members of a larger group called Climate Direct Action—had flipped the emergency shutoff switches on four oil pipelines back in 2016. The group is sort of like the antifa of climate activism in that the term “Valve Turner” describes a tactic more than a group. You’re a Valve Turner if you locate and flip a pipeline off-switch. The usual M.O. afterward is to A) get arrested, then B) claim in court that you had to shut it off because burning oil was interfering with the livability of Earth—the “necessity defense”—and then if all goes according to plan, C) the judge may dismiss the charges, and you’ll go free.

In an October 2017 opinion about the Valve Turners’ case, a Ninth Circuit Court judge named Robert Tiffany tacitly acknowledged that climate change posed a significantly greater capacity for harm than the extremely petty property crime involved in switching off a pipeline. As Kelsey Skaggs, the lawyer for the valve turners put it in a press release, “the court acknowledged both the scope of the climate crisis and the people’s right to act when their leaders fail them.” In this (probably very lucky) case, the legal system recognized that our institutions are supposed to protect us, but the extent of their failure to do so is sufficient to justify physically turning off big machines owned by other people, against those people’s wishes, if those machines put fuels into the market for transportation and electricity.

“We must stop the flow of fossil fuels as a society,” Michael Forster, one of the Valve Turners arrested in 2016, told The Associated Press. “You can argue about the best, or better, ways to do it, but we haven’t done it yet, and we’ve run out of time.”

To be clear, valve-turning probably doesn’t keep a single molecule of CO2 or methane out of the atmosphere right then and there, but dealing with the repercussions of a pipeline being turned off makes the oil business incrementally less profitable on that particular day. And speeding up the downward slide in the profitability of fossil fuels is the real goal.

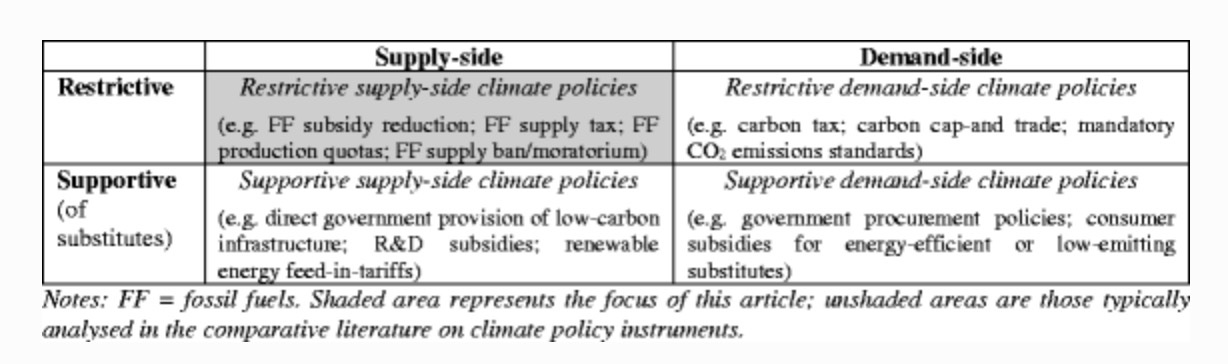

The same concept exists in the more staid world of climate change economics, where anyone proposing restrictive supply-side policies is basically a valve turner whose primary tool is the policy paper instead of the wrench. In their most extreme form, supply-side policies would be policies that ban fossil fuels—though probably just in limited circumstances.

Instead of bans and restrictions, the climate policies most favored by the super-elite masters of the universe like Bill Gates involve subsidizing and loudly cheerleading renewable energy sources. Gates claims that the correct approach is to use the market to “push” against fossil fuels, economically speaking, and “pull” fossil fuels down, economically speaking. “The push is the R&D,” he told The Atlantic in 2015, adding, “The pull is the carbon tax.” This talk of pushing and pulling sounds like gibberish to me, but that’s probably just my feeble brain failing to comprehend the genius of the market system.

But a 2018 economics paper by Fergus Green and Richard Denniss called “Cutting with both arms of the scissors: the economic and political case for restrictive supply-side climate policies,” gently pushes back against Bill Gates, and makes the mainstream case for supply-side policies in addition to demand-side ones. Green and Denniss categorize policies by “side”—supply or demand—and whether they’re “supportive” or “restrictive,” then they organize all methods of combatting climate change into quadrants:

Pretty bland stuff, so let’s replace fossil fuels with Nazis to make understanding these quadrants a little more fun. You can use “supportive” tactics, which is like helping your allies who are fighting against Nazis, or you can be “restrictive” which is like actively hindering Nazis in some way. Demand-side policies can be compared to more indirect war strategies, like diplomacy and aid money, while supply-side policies look more nakedly hostile.

A supportive demand-side strategy is something like a tax rebate on an electric car, so in our Nazi analogy that’s a little like giving aid money to the USSR to build things they need for their war effort like hospitals. A supportive supply-side strategy such as a government constructing electric car charging stations and letting people use them for free would be a little more direct in the Nazi analogy, like giving weapons to the USSR. A restrictive demand-side policy is something like a carbon tax, indirectly punishing fossil fuel use with taxes and higher emissions standards, and that would be like cutting German communications cables and sanctioning German allies.

Last but not least, we have restrictive supply-side policies, including bans, and any sort of production moratorium—governments doing the same thing as the Valve Turners, basically. For some weird reason, these policies represent a sort of economic rubicon that no one wants to cross.

And that might be because back in our Nazi analogy, this is where we get into “the killin’ Nazi business,” to paraphrase Inglourious Basterds. I submit that if you were an American in 1942 who only had a vague idea who Hitler was, but your son was suddenly in North Africa killing Nazis, the nature of the once very complicated struggle against Nazi aggression probably became a lot easier to grasp.

I’m simplifying, yes (US cars weren’t powered by Nazis when US soldiers started killing them). I’m also making lavish use of the classic reductio ad Hitlerum logical fallacy, sure. But even if we delve back into the dry, economics lingo of the Green and Denniss paper, we find an urgent need for these kinds of policies. For one thing, the authors point out, we’ve known for a while about demand-side policies having the potential to make climate change worse by causing energy companies to hurry up and burn fossil fuel while they can, according to the paper.

The risk of future policy change to the current value of a resource—for example, the risk of a future carbon price reducing the current value of coal resources—can induce resource owners to bring forward their extraction of that resource, thereby reducing its market price, causing an increase in its consumption (a phenomenon dubbed “the Green Paradox” […]) Supply-side policies can be a straightforward means to mitigate the impact of the Green Paradox.

To see a likely example of the Green Paradox in action look no further than Exxon’s pre-COVID 19 plan, according to documents leaked earlier this month, to rapidly scale up its greenhouse gas emissions by 17 percent over the next five years.

So given that climate change-related disasters are already here, and they’re getting worse, and given that even economists are worried that restricting the supply of fossil fuel might be (gulp) necessary, and that demand-side policies might be speeding up climate change, it’s bananas that the question, “How soon can we be done with fossil fuels?” is almost never asked.

According to David Roberts of Vox: “There is a bias in climate policy shared by analysts, politicians, and pundits across the political spectrum so common it is rarely remarked upon. To put it bluntly: Nobody, at least nobody in power, wants to restrict the supply of fossil fuels.” Needless to say, even fewer people want to talk about restricting the supply down to zero.

But the scowling analysts, politicians, and pundits have, in all likelihood, stopped reading by now anyway, so pardon me while I engage in a little bit of pure fantasy by imagining a total abolition scenario for all global production of fossil fuels. This could be accomplished with a binding international treaty, setting a date in the near future after which machines that mine, drill, refine, or otherwise produce fossil fuels have to be permanently taken offline under pain of sanctions, forcing nearly everyone in the world to scramble like ants in a kicked anthill and come up with energy solutions fast—ad hoc or not.

Obviously some sort of big, global fossil fuel off-switch event is less a policy platform than a rhetorical device. A protest slogan. A thinly-veiled threat that should be hanging in the air when policymakers whine about the impact of a relatively minor demand-side policy like the creation of a wind farm or something. As a bargaining tactic, a fossil fuel ban should quietly be there on the table as the ugliest alternative, because as it is, the alternative on the table at every negotiation is “do nothing,” and that’s what our betters keep picking for us.

“Abolish fossil fuels” could act as the extreme guiding principle that shakes leaders out of their complacency and apathy, and drives home the need for serious and speedy reform. As with “abolish the police,” if “ban fossil fuels” were a trending topic, people would be googling crazy-but-in-retrospect-sort-of-understandable things like “Is gasoline a fossil fuel?” Explainer articles would suddenly need to be written. It might go a little something like this:

Q: Wouldn’t people suffer and starve without fossil fuel energy?

A: Well they certainly would if we banned fossil fuels all at once without any advanced notice, but since that’s not on the table, it’s necessary to work out how it can be done as soon as possible without denying anyone their basic material needs. The existing Green New Deal plans have a lot to say about how this kind of thing can uplift the poor and marginalized.

Q: What if everyone’s needs are met, but some companies lose money?

A: I can live with that.

Q: Wouldn’t right-wing populists and racists use a policy like this to their advantage?

A: Maybe. But they already appear to do that with every climate policy as it is. According to economist Matthew Lockwood of the University of Sussex, not enough research has been done to understand the connections between climate policies and things like material insecurity, racism, and hostility to elites. “Any effective response to the populist challenge will need to rest on such an understanding,” Lockwood writes.

Q: Could museums and universities receive special dispensation to make small amounts of fossil fuels for historical recreations?

A: Probably.

Q: Shouldn’t developed economies with high carbon footprints ban fossil fuels first, while developing economies ramp down more slowly?

A: Probably.

Q: Is anyone in the position to volunteer to live fossil fuel-free lives now so they can ease the burden of the transition on the rest of us?

A: If you’re interested in this, I for one will not stop you. But either way, this would not be a reflection of someone’s morality or lack thereof.

Q: Won’t things like plastics, vaseline, and other petrochemicals become expensive without oil drilling?

A: Maybe! More research is needed in this area for sure.

Q: If fossil fuels were illegal, would the cops come beat me with nightsticks if I used a charcoal barbecue?

A: I can’t control the cops, so I don’t know. But no ban of this sort should have any bearing on what individuals do in their homes. It should exclusively be a ban on the production of fuels. Maybe there could be a program where you could voluntarily trade your supply of charcoal for, say, a free induction-powered barbecue.

My book, The Day It Finally Happens (now in paperback!), was a collection of exercises in this type of hypothetical thinking. If “The Day the Global Off-Switch Is Thrown” had been one of my book chapters, I know some of the scary scenarios I probably would have included: things like blackouts, dry gas pumps, power shortages for electric cars, business closures, hospitals that can’t function, deaths from heatstroke, people freezing in their homes, fascist scapegoating of religious and ethnic minorities, and widespread political collapse.

But it would also be about the effects of this kind of brinksmanship in the lead-up to the big day. If we all knew Off-Switch Day was coming in, say, ten years, then the next ten years would take shape for us. We could worry less about whether politicians have the cojones to pass a Green New Deal, or move forward with “The Biden Plan for a Clean Energy Revolution and Environmental Justice,” because the change would already be visible all around us. All the businesses in your neighborhood would be busy retrofitting their buildings with solar panels and batteries, and updating their obsolete appliances.

A well-planned, progressive Global Off-Switch Day lead-up would subsidize similar updates for people’s homes, and workers at oil pipelines and coal power plants would transfer to high-paying jobs in the renewables sector, because labor would be in high demand if there were a frantic global scramble for green energy.

I’m not saying a fast ramp-up to a global fossil fuel ban is a perfect solution. I know better than to do that. It would be far from perfect. But everything we’ve tried so far has already been a disaster, and more disasters are on their way.

In the meantime, nothing like this is even being discussed, and climate change is increasingly being reduced to a meaningless consumerist culture war, pitting Republican SUVs against Democrat Teslas and vegans against whatever Jordan Peterson is. In the face of this ever-deepening stupidity, valve-turning seems like the next best thing to a policy solution. So here’s my advice if you run an energy company and you don’t want desperate climate activists showing up and turning off your precious oil pipelines: stop giving desperate climate activists such a compelling and legally defensible reason to shut them off.

Hello person who read all the way to the bottom. If you’re enjoying this newsletter, please subscribe and spread the word. I’m hoping to post these more often, and have a paid tier, and do more in-depth reporting, etc. Earning more subscribers is the only way to make that possible. —Mike

Fantastic work